Tell us briefly about Phutung Research Institute. What are the short and long-term goals?

Phutung Research Institute is an organization of people sharing a strong conviction that science and technology is the only effective way to solve major societal and economic problems of developing countries. It is probably the first and only institute of its kind in the world. It is unique for three main reasons, (1) its focus on cutting-edge scientific research specifically aimed at solving concrete problems of the developing countries, (2) its stated policy and practice of engaging non-scientists in its executive body, (3) its approach to involve communities and public as the drivers of the research.

For the short term, we are focused in Nepal, and in the long term we see ourselves expanding into other developing countries, and subsequently to developed countries.

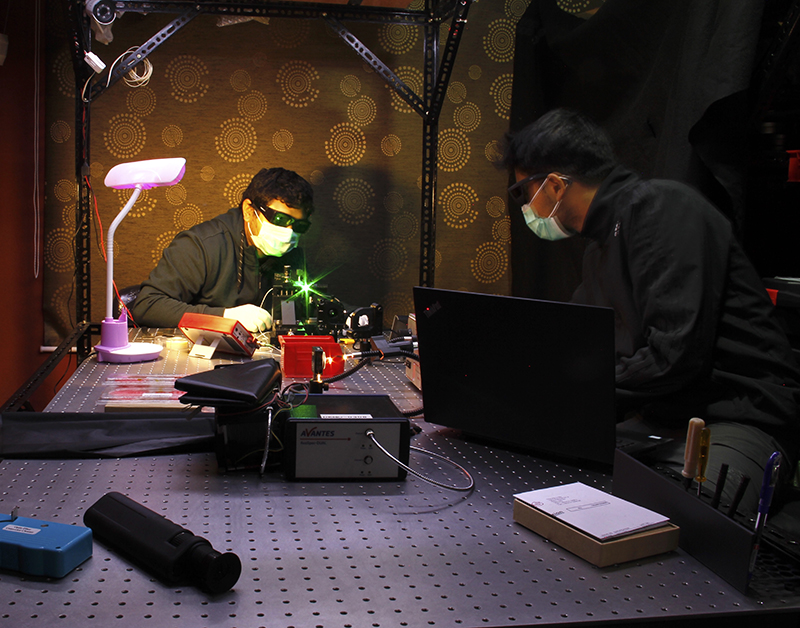

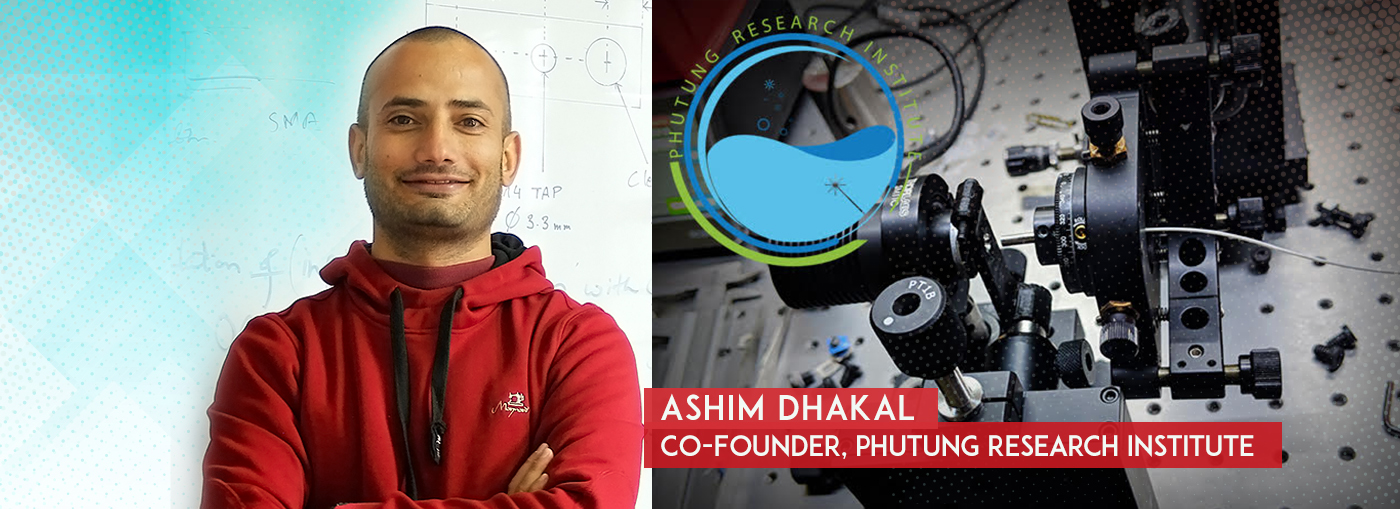

Phutung scientists working in their Photonics lab for their projects related to spectroscopy and optical coherence tomography

What are different research activities going on in Phutung? Also, tell us about your multidisciplinary approach to research.

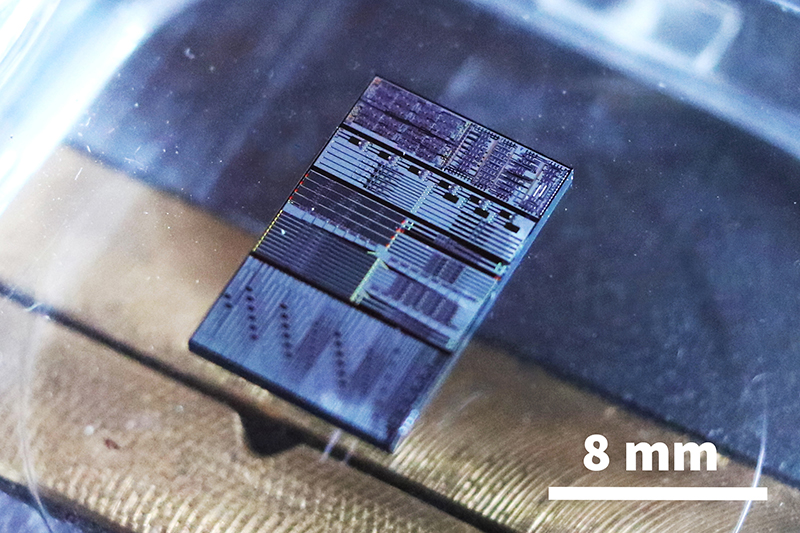

We are working on several research projects in Phutung. The research domains range from agriculture to fire safety. Not all of these research projects are well-funded, but we are slowly but steadily making progress in our multifarious research objectives. Some projects are well-funded and very active. For example, one of our projects aiming to develop nanophotonic imaging technology (see figure) for diagnosing early stages of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease – the number one killer in Nepal and other developing countries – is generously funded by EPSRC-GCRF in the UK. This project has already led to well-received publications in reputed international conferences like IoP-Photon 2018, and IEEE-Sensors 2018. Our another active research is focused on developing a low-cost UV-Raman spectroscopy system for food and water safety analysis, and has been funded by TWAS. In the context of this project, we have invented a very interesting instrumentation that we will be prototyping soon.

An example of the nanophotonic chip being developed under EPSRC funded Phutung project

You have mentioned that ‘We see “lack of plentitude” itself as a research challenge’. Please elaborate on this.

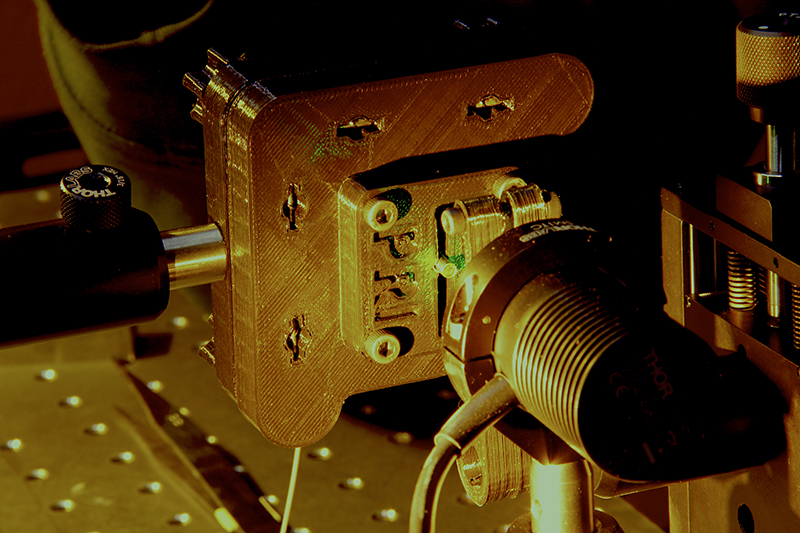

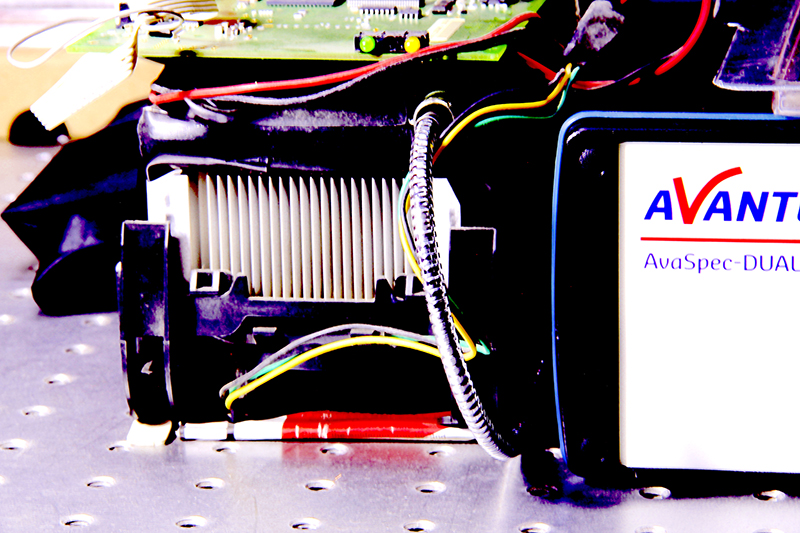

Thanks for asking this question. “Lack of plentitude”- by which we mean lack of resources generally thought essential for conducting research – is a very important aspect of research in poor countries like ours. Ideally, scientific research needs precise and very costly equipment. However, it is generally possible to do the same research at lower cost if we design the research well. This is an extra research challenge that richer institutes are not forced to grapple with. However, it is also an opportunity, as it forces you to think creatively of ways to be cost-effective. For example, we have 3D-printed optomechanical devices worth thousands of dollars (see figure). We have cooled our optical detectors using peltiers and old computer parts (see figure), saving us another thousands of dollars. We have also modified commercial imaging microscopes for spectroscopic microscopy. We always think about minimizing the cost of research without affecting the quality.

A three-axis kinematic mount, one of the highly expensive optomechanical components, developed and manufactured in our lab using 3D printers

Charge-coupled device cooling system developed using Peltier coolers and old computer parts

Please tell us about your own career journey. What was your personal motivation to found Phutung Research Institute?

I started as Operations Engineer at NCell (then, Spice Nepal Pvt Ltd with MeroMobile brand), and soon became Team Leader and Executive Engineer in the operations team. It may be a bit interesting to tell you that I also led a sort of “rebellion” in the company against some bad managerial decisions, leading to the establishment of the Trade Union in the company, of which I am the founding president. Science has been my passion since childhood, and therefore I moved on to pursue my scientific career with a M. Sc. in Photonics with Erasmus Mundus scholarship, and eventually a PhD at Ghent University and imec.

Where does Nepal stand in terms of conducting world-class research? Do we even need to aim for world-class research or instead try to solve our local practical problems?

Nepal is ranked 109 among 126 countries in Global Innovation Index Report 2018. In terms of Human Capital and Research, it is ranked 120, while in Knowledge and Technology Output Impact it is ranked 124. There are in total 14 patents filed so far in Nepal’s patent office history. These figures show where we stand in terms of research and innovation in the world stage. Clearly, we are not innovating at all to solve our local problems.

Impact is the sole criteria to rate a research. A genuine research or an invention aimed at solving a concrete practical problem, whether local or global, is in itself a world-class research/invention; because, it will have significant impact on the society. The nice thing about solving a problem in the developing world is that the solution is equally relevant for rich countries, therefore it has higher impact compared to the research done for developed countries. The converse, most of the times, is not true.

What are your observations about research ecosystem in Nepal? Do you think collaboration is not just an ideal goal but also a practical necessity? Is our ecosystem robust enough to allow constructive competition?

Well, there is almost no research ecosystem in Nepal. Therefore, one of our priorities is to build such an ecosystem. To this end, we are teaming up with other budding research organizations in Nepal (like, KIAS, RIBB, CHDS, KRIBS, NAAMII, ARC) to form an alliance. The alliance will coordinate with the government bodies to formulate policies and laws that are conducive to scientific and technological research. Collaboration in scientific research, Nepal or anywhere, is a practical necessity because it provides expertise and resources that you need, but do not have. It is primarily a practical necessity, therefore, it is an ideal goal – sometimes difficult to achieve because of what you called “competition in research”. In Nepal, competition is rather irrelevant as our ecosystem is almost non-existent.

In your Phutung journey, what are the lessons you learnt on a personal and institutional level?

The support I got from friends, family, acquaintances, and even commercial institutions in my Phutung journey was exceptional. The donations, grants, sponsorships, discounts, partnership offers and support we have received for Phutung is truly phenomenal. This, I guess, is because Phutung is a selfless social enterprise, and because people have appreciated that I, and many of our members, have given up our careers as well as savings for this enterprise. A major lesson that I have learnt during this journey is that if your aim is noble, you will be able to face dire challenges easily, because you will receive support from most people. This is probably how the theory of Karma works!

On an institutional level, I have learned, and am still learning, the details of institutional management, the real situation of Nepali bureaucracy, and have identified key problems of the country.

Tell us about a time you had serious doubts about your own ability in the fields you chose. How did you overcome that?

As in any enterprise, there are ups and downs, emotionally or otherwise. However, I do not remember having any serious self-doubts. Sometimes, my self-confidence is just a freaky idiosyncrasy. Yet, it has allowed me to take high risks, therefore, at times, produce exceptional results; and of course, at times, very bad ones. I think self-confidence, if rooted in convictions developed through scientific observations and logical reasoning, usually produces exceptional results.

Tell us about the role of mentorship in your professional life.

Of course, mentors have been very important to shape my professional life. I am forever indebted to my PhD advisor Prof. Roel Baets who has shaped me as a scientist and, to some extent, also reshaped my personal character.

What is the best career advice you have ever received?

A career is a complicated thing, it gradually evolves with individual situations, opportunities, convictions, and passions. Hence, I personally do not believe in the idea of “the best career advice” that would change things; therefore, I can not recall such an advice.

The career advice you wished you received in your twenties.

I do not think any particular advice would have changed my career, again, for the reasons I discussed before. If you are asking me to advise your readership in the twenties, I would advise them to face any problem at hand, to understand the nature of that problem, and to work passionately to solve them. I believe that solving problems at hand is the only key to general well-being and eventual success.

How can the youth of Nepal participate in Phutung Research Institute?

Please check pinstitute.org/careers for vacancies.

Your final words of advice for the youth of Nepal who want to realize their own bold visions.

If you have a “bold” vision, make sure the vision is viable – base your arguments with logical reasoning and concrete scientific facts. Discuss the vision with some critical people, who will help you to understand the risks and benefits, and to identify the path ahead. Rest is to work hard and methodologically to solve the inevitable problems you will be facing as you progress. Again, let me remind, solving problems at hand is the key to success.

Best wishes to our pioneer engineer scientist Ashim Dhakal and his team for this innovative journey to the success of Nepal.

Great to see such work being done in Nepal.